37. The Motherlode

Wherein I come home with an absolute haul of books

In my last issue, I put forward two theories about how cookbooks find their way onto thrift store shelves. To recap:

They were so wildly popular in their day that it was almost inevitable that at least a few would get donated. There are so many copies of the Company’s Coming series in the world that it would be odder not to find one.

They “suck,” where sucking is defined as no longer being of any use to its owner. If you’ve just learned you’re lactose intolerant, The Complete Dairy Foods Cookbook, by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Shipping News and Brokeback Mountain, Annie Proulx, would suck for you.

But there is, I believe, at least one other way that cookbooks find their way to thrift stores. I call it, “The GTFO.” Someone who doesn’t know (or care) anything about a whole bunch of books is desperate to get rid of them and donates the lot all at once. Maybe it’s the estate of a distant relative or a landlord cleaning out the apartment of an evicted tenant. (Editor’s note: HEY!) They just want it all gone. And if your timing is lucky enough, you don’t have to pan for gold in the cookbook section; sometimes you hit a seam.

I rarely find something that interests me enough to wait in line to buy it. If I do, it’s usually just one book. But a few weeks ago, I hit a seam and walked away with my arms full. And I have to think that most of them were the result of someone who just needed them gone. They were so interesting, unusual, or noteworthy that someone not caring at all about them is the only explanation for how they wound up being donated.

They fall into a few categories:

The Gold Standards

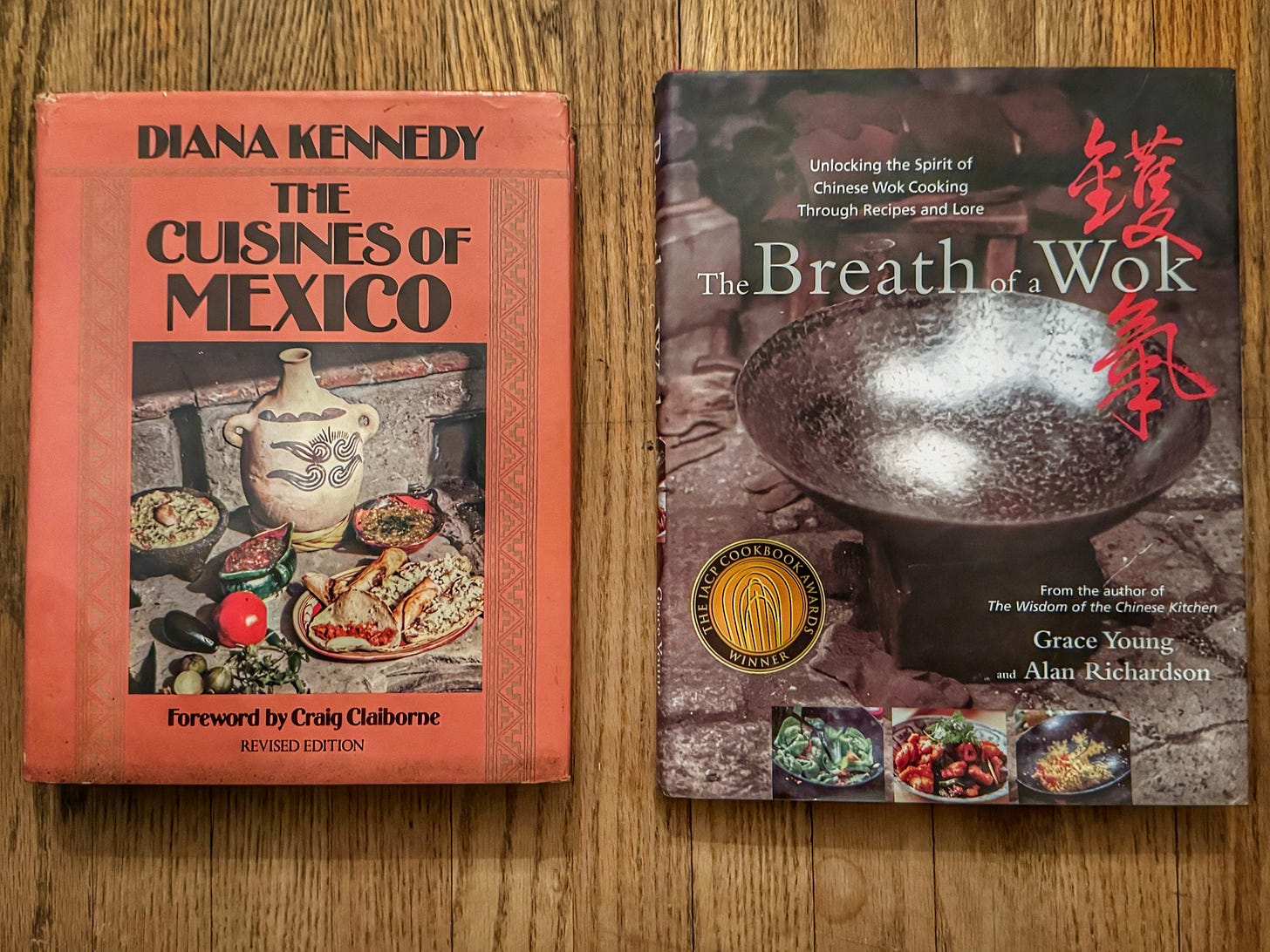

I wasn’t looking specifically for either of these books, but as soon as I saw them, I knew they were coming home with me. They are both seminal works and I was surprised and excited to find them.

The Cuisines of Mexico by Diana Kennedy

As Julia Child1 is to French cooking in America, so Diana Kennedy is to Mexican cooking. Inspired by her time living in Mexico in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s2 and bolstered by additional research while writing it, Kennedy’s 1972 book was one of the first books in English to look beyond Tex-Mex cooking and introduce the widely varying regional styles of Mexican cooking to the English-speaking world (hence “the Cuisines of Mexico”). Kennedy, who died in 2022, moved back to Mexico from New York in 1976, wrote eight more cookbooks, and spent the rest of her life combing the Mexican countryside in her four-wheel drive in search of more traditional recipes and techniques. Many other cookbooks would follow in Kennedy’s steps (including ones by writers who were born closer to Mexico than, for instance, Loughton, Essex, as Kennedy was), but Kennedy opened the door.

The Breath of a Wok by Grace Young

One of the most recently published cookbooks (2004) to be inducted into International Association of Culinary Professionals Culinary Classics, Young’s book is credited with giving wok hay, the smoky, seared flavour that is so characteristic of foods cooked in a a restaurant wok, its English translation, “the breath of a wok.” As the IACP describes it, “With award-winning photographer Alan Richardson, Grace travels through the U.S., Hong Kong and Mainland China, cooking and talking with professional chefs, home cooks and cooking teachers to discover the myriad secrets of the wok—and life itself.” To give you an idea of how exciting a find this was, when I posted it to a Facebook story, I promptly received a message from the guru of the Toronto food scene, Suresh Doss, that just read, “Ohhhhhhh.”

The Yardstick

Japanese Home Style Cooking by The Better Home Association of Japan

This is not a widely acknowledged classic in its category. In fact, I had never heard of it before finding it,3 but I knew in an instant it was a book that I had been looking for without ever knowing it. Its focus on the kind of homey, casual dishes I knew nothing about until I moved to Japan is something not covered in a more formal text like Shizuo Tsuji’s classing Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art. I’ve written before about how I sometimes surprise myself with how strongly I support the orthodoxy of some foods, like club sandwiches and shrimp cocktails. Similarly, while I appreciate the more personal and specific approaches to food in books like Nancy Singleton Hachisu’s Japanese Farm Food and Sonoko Sakai’s Japanese Home Cooking, this book focuses on the straight-down-the-middle, standard versions of dishes I loved when I lived in Japan, like niku-jaga4, oden, and agedashi-tofu. I’m all for people adapting the classics to suit their tastes, but I want to understand what makes them classics first. This book should help with that.

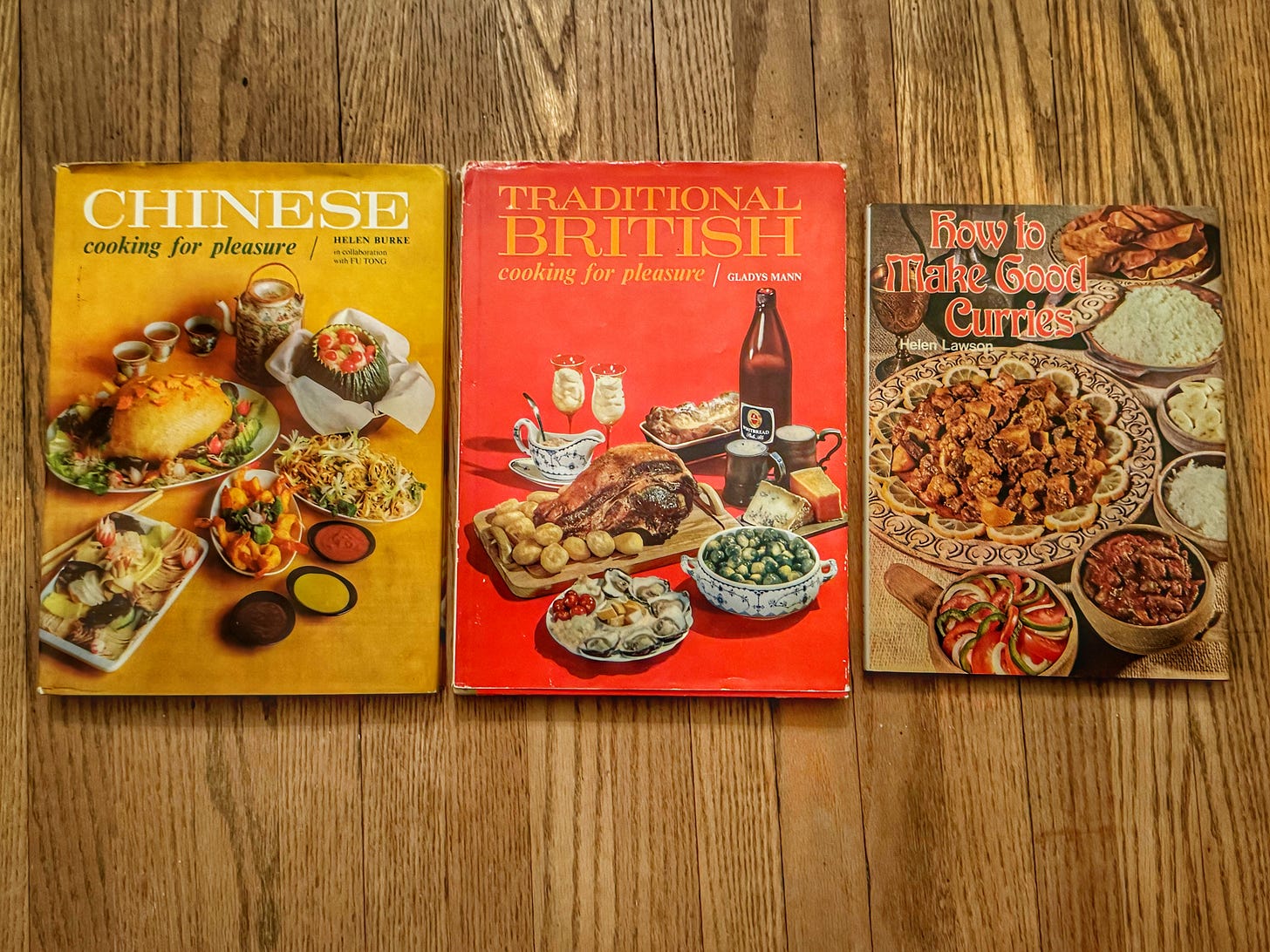

The Time Capsules

I had to have a few books in spite of the fact that I probably won’t get much use from their recipes. There’s no way to describe them other than, “of their time.” Their value now is as historical documents.

Traditional British Cooking for Pleasure by Gladys Mann

Chinese Cooking for Pleasure by Helen Burke in collaboration with Fu Tong

How to Make Good Curries by Helen Lawson

From what little I’ve been able to track down online, Cooking For Pleasure was a series of books published by Paul Hamelyn in the mid-to-late 60s. They seem like a precursor to the more familiar5 (to North Americans) Time-Life Foods of the World, which first appeared in 1968. In addition to the British and Chinese volumes, there are also books about Caribbean, French, Italian, Indian, Jewish, and “Far Eastern” cuisines, as well as at least several more.

I don’t dare speculate as to how faithful the Chinese recipes are to their original inspirations. At first glance, there are a few more dishes that call for canned water chestnuts and bamboo shoots6 than you might find in a cookbook today, but also many recipes that require less common ingredients like ya cai and MSG, which the book refers to as “Ve-Tsin.” As for the British recipes, you’d almost expect a book about British cooking in the 1960s to tell you to boil everything to death. (To be fair, a good portion of the chapter on vegetables, recommends a 10-15 minute simmer for most things.) But with chapters with devoted extensively to Bakeoff-worthy baked goods and preserves, pickles, and jams, the greater, older traditions of British cooking have their moments as well.

Also published by Hamelyn, this time in 1970, How to Make Good Curries is an omnibus that covers Indian, Pakistani, “Ceylonese,” and Malaysian (among others) dishes, as well as recipes from less expected places, like Hawaiian curried lamb and Australian curried rabbit. There are also recipes for curry accoutrements like rice, chapatis, chutneys, and sambals. Again, I am in no position to pass judgement on how much the recipes are or are not bastardizations of more traditional ones, but, looking at the two recipes for garam masala, neither strikes me as very different from recipes I have used more recently. And I may just have to give Calcutta Meat Balls, which seems like one of the less traditional choices, a try.

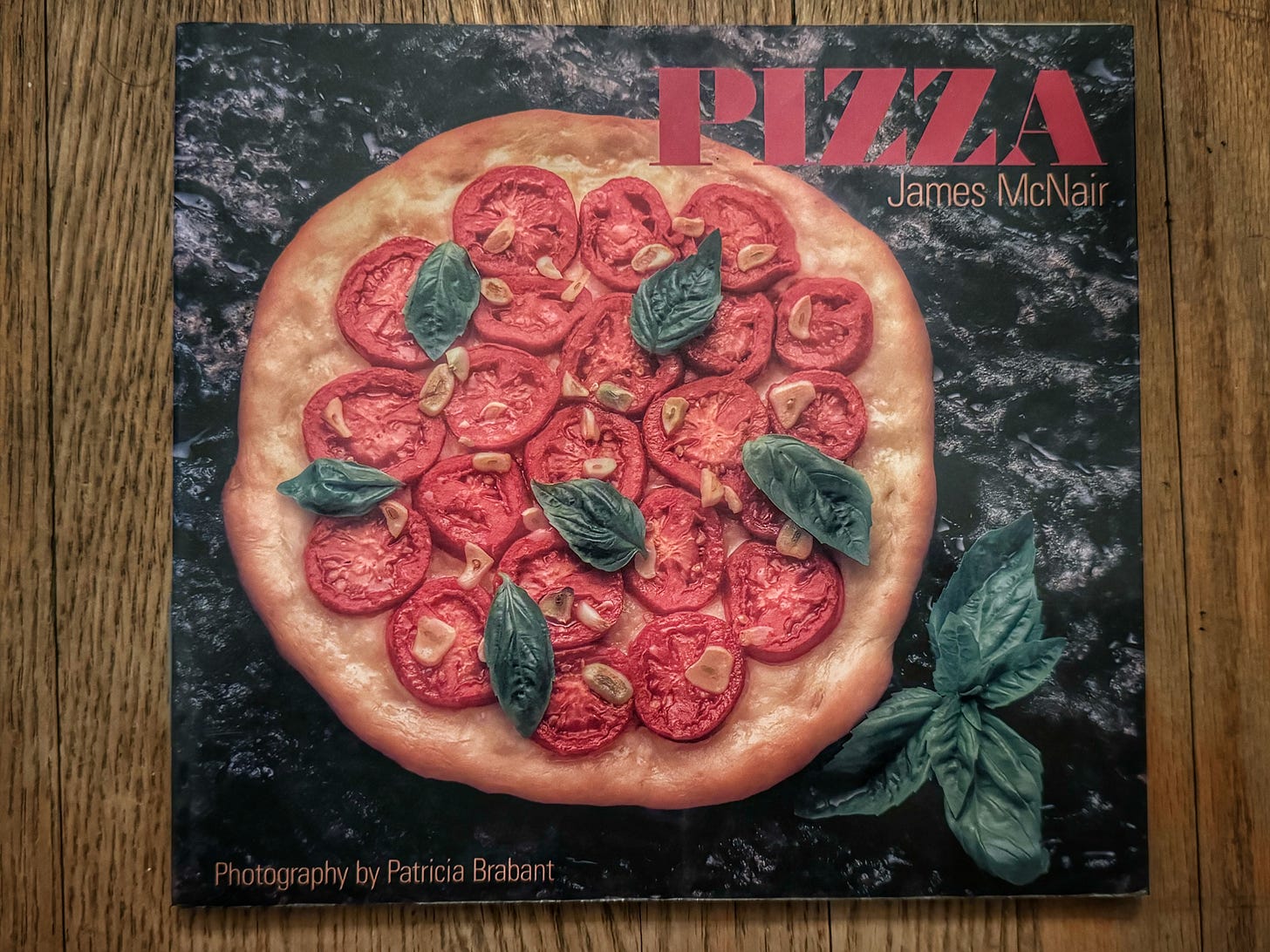

The White Whale

And finally, I mentioned last issue that there is one cookbook (actually a series of cookbooks) that I immediately scan shelves for before seeing if anything else is interesting. For the first time in years, I was able to find one.

Pizza by James McNair

Like Dave Nichol’s influence on food and groceries in last week’s issue, it’s hard to overstate the effect McNair had on the entire cookbook publishing industry with the 40+ titles he published starting with 1985’s Cold Pasta. His innovations were several. Instead of being a collection of recipes for every course of a meal, or every type of dish in a cuisine, each of his slim, square books focused on a fairly narrow topic, like cold pasta, pizza, salmon, rice, or squash. And instead of the occasional black and white photo or illustration (or possibly a section of colour photos inserted as a section) there was always a well-staged, colourful photo of every finished dish on the page opposite the recipe. It seems odd to think that these weren’t always the case, but before McNair, they weren’t.7

I had copies of Pizza and Rice in university, but they got lost in the shuffle of growing up. Looking through Pizza now, with the growing (and sometimes painful) knowledge I’ve gained in recent years, it’s not something I would follow very faithfully. Amateur pizza making has come a long way since the book was published in 1987. The same dough, measured volumetrically instead of by weight,8 is used for every style of pizza, which would elicit howls of objection from every pizzaiolo in Naples. He gives the option of baking on screens, which reduces the transfer of heat from the baking surface to the dough and is the hallmark of someone who has never learned to launch a pizza from a peel.9 And, most horrifically, he gives you the option of rolling out your dough with a pin!10

I have no plans to use Pizza and yet I’m so happy to have found it. It’s a comfort to have around and flip through.11 There is currently a lot of 21 of McNair’s books on eBay, but the $210 (CAD) price tag is a little steep for me. I think instead I will continue to keep my eyes peeled while thrifting. It only took me a few years to find Pizza,12 so I should round out my collection in 30 or 40 more years.13

What you are potentially consuming…

Last issue, I mentioned I had the urge to buy up all of the great books I see while thrifting but already own, so I could redistribute them to cooks who will put them to good use. Since then, I have decided to put my money where my mouth is. First up is an almost mint-condition copy of Mark Bittman’s How to Cook Everything - the Completely Revised Tenth14 Anniversary Edition. Mark Bittman is an out-of-touch dinosaur as a person, but HTCE is an all-time great book, especially for someone who is just finding their feet in the kitchen. It has hundreds and hundreds of recipes, diagrams, and charts that cover, well, everything. I still consult it if I’ve forgotten, for instance, at what temperature winter squash should be roasted. If you’re already a confident cook, the book would also make a great gift for one of your culinary protégés.

So here’s how this will work: by the time you are reading this, I will have posted a picture of the book on my Instagram feed. (What do you mean you’re not following me on Instagram?) In the comments, tag someone who is not a subscriber who you think should become one. Each time you tag someone, you’ll get one entry to win the book.15 I’ll include some terms and conditions that have not been vetted by any legal department as well. Good luck!

What’s on the menu…

The Hamburger at The Golden Peacock

I was meeting up with a couple of friends a few weeks ago and The Golden Peacock, the year-old, cocktail-y sibling to the excellent Donna’s, seemed like a good halfway meeting point. It has a short menu with just ten choices including dessert, but the length is irrelevant, as it turns out, because I will just be ordering their burger whenever I go. Much like the Whopper it was reportedly inspired by, it’s neither a super-thin, super crusty smashburger or a thick, pub-style burger. It’s something like the best backyard cookout burger you’ve ever had—you can taste the stripes of char from the grill bars. Even days later, we could not stop texting about how good it was, especially with an order of the equally excellent, thick-cut fries on the side.

And, to some extent, her co-authors of Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle.

The Child-Kennedy parallel doesn’t end there. Child fell in love with French cuisine while her husband was posted in Paris by the State Department. Kennedy first experienced Mexico when her husband was posted in Mexico City as a correspondent for The New York Times.

For good reason, since there doesn’t seem to be much online about it, other than the title. There is absolutely no information that I could find about the non-profit that published it, The Better Home Association of Japan. That hasn’t stopped it from being included on the Japanese Embassy in Canada’s list of recommended books about Japanese hobbies, however.

The first few times my colleagues ordered this during a post-work izakaya visit, I was very confused about why there was a dish called “Mick Jagger.”

And more gorgeous. And more authoritative.

No knock on either. I put both in a some stir-fried baby bok choy tonight that, while tasty, I would most generously describe it as “vaguely Chinese-inspired.”

I could (and one day might) go on and on about McNair. Or rather, I could write a bit more. For someone who, as of 1991, had sold nearly two million cookbooks (almost as many as Martha Stewart), there is very little written about him. And since 2013, the online McNair trail has gone completely cold.

That is, he measures his ingredients in cups rather than by weight. The amount of flour measured in cups can vary wildly, depending on how firmly or loosely it’s packed and is a bad idea for most baking.

OK, Chicago tavern-style pizza is the exception, but McNair doesn’t have a recipe for it.

I realize the urge to re-obtain the trappings of your younger self is pretty classic middle-aged man behavior. I’m fine with that. You should see the eBay, Kijiji, and Facebook Marketplace alerts I have for guitars I used to own. By comparison, picking up the occasional McNair for $5-10 doesn’t seem so bad.

I really should have a theory as to why someone who sold as many books as McNair is so rarely found in thrift stores. I don’t. I think I’m too close to the subject.

I have since bought copies of James McNair’s Cold Cuisine and James McNair’s Breakfast, so only or 19 or 20 more to go!

There’s also a twentieth anniversary edition, released in 2019.

Cut to me praying the winner lives within driving distance of me so I don’t have to ship this 4.5-lb monster.