22. Noodling

Getting a taste of once-home

Of the almost-nine years I lived in Japan, I was almost always in Osaka. And in Osaka, if you are going to eat non-ramen noodles, you’re most likely to eat thick, wheat-based udon. (In Tokyo, thin, buckwheat-based soba is more popular.) In the 20-plus years since I moved back to Toronto, I’ve had udon on a few occasions and it has mostly been disappointing. Unpleasantly gummy noodles that lacked the slippery springiness of udon in Osaka. Many, I suspect, were made from the plasticky, shelf-stable, pre-cooked noodles available at Asian supermarkets.

Bushi Udon Kappo was open for a hot second not too far from the house, but it was gone before I ever made it there1. Ematei had a very nice nabeyaki udon (hotpot style) that I enjoyed, but it’s gone now too. But a branch of the New York udon shop Raku opened downtown in 2019. I found myself working nearby a few months later and stopped in for lunch. At last! Slippery and nicely chewy noodles in a deeply savoury, soul-warming broth. The kamonan, with duck and green onion, quickly became my standard order. But alas, I haven’t stopped in for lunch anywhere in the last two years, of course, so my kamonan itch went unscratched.

Until I decided to scratch it myself.

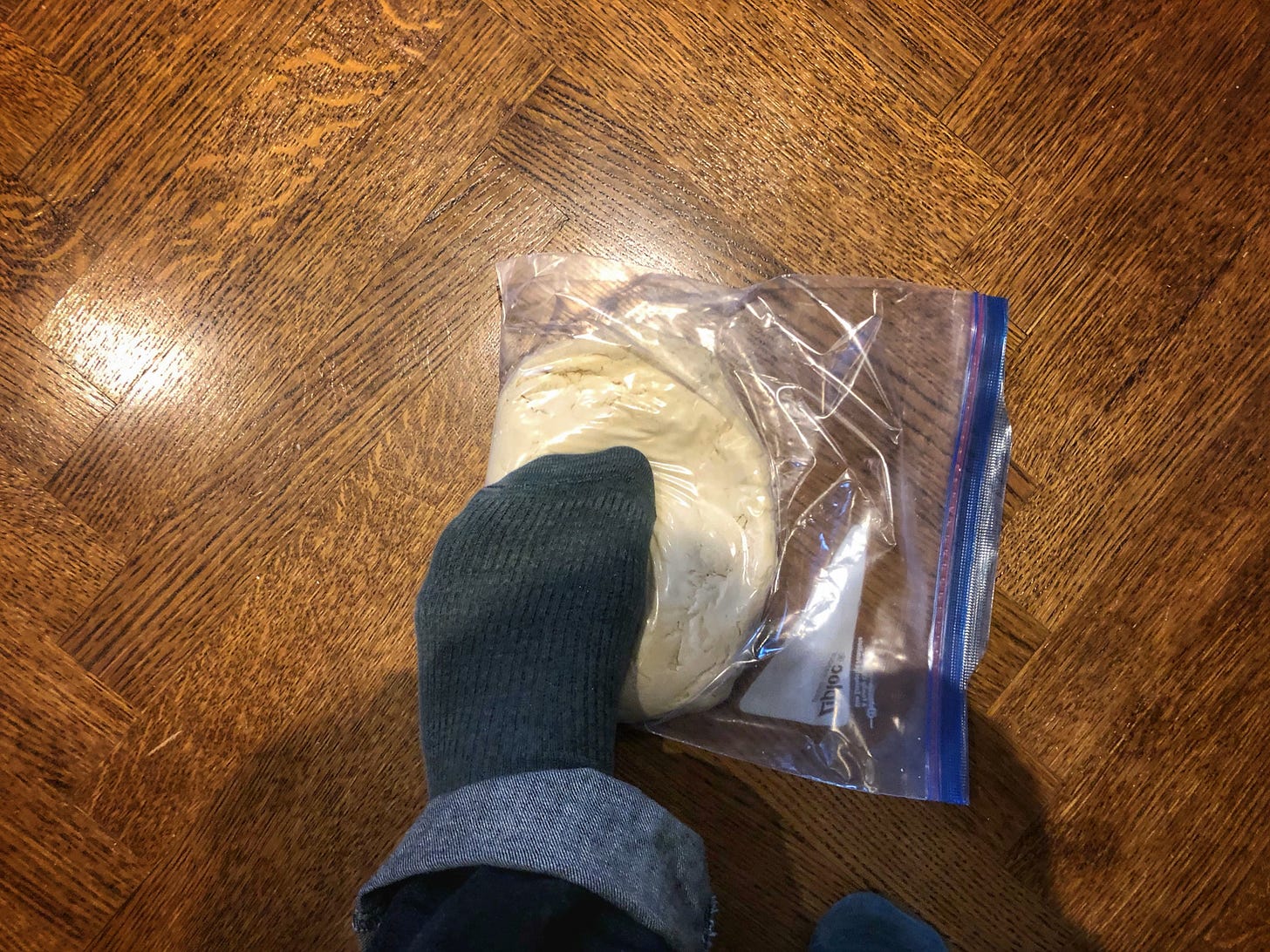

Shizuo Tsuji has a recipe for the related tori namba2 udon in Japanese Cooking: A Practical Art, which replaces the duck (kamo) with chicken (tori). He also has a recipe for the noodles, but I found Sonoko Sakai’s recipe in Japanese Home Cooking more appealing, for one because after mixing the dough ingredients together (and a 30-minute autolyse3) it requires you to put the dough ball into a one-gallon4 Ziploc bag and knead it with your feet for five sessions of 100 stomps each.

After a long rest to allow the gluten to develop, the dough gets rolled out into a large square, folded over on itself, and cut into noodles.

I made a rookie mistake here and cut the entire sheet before trying to separate the noodles, some of which had re-attached to their neighbours in the time it took to cut everything. Next time I will stop a few times to separate and make cornstarch-dusted nests with what I have just cut.

While the noodles boiled for 15 minutes, which seems like a long, long time to cook pasta but actually worked very well, I poached chunks of duck breast in a broth made from dashi, light and dark shoyu, salt, and sugar. With one minute to go, I tossed some chopped green onions into the broth as well.

Was it as good as Raku? C’mon, of course it wasn’t. It was definitely the second-best bowl of udon I’ve had in a long, long time. It’s time-consuming, but any extra noodles can be frozen for later. I’m eager to try again, although the next time I will try making it with the pasta attachment on the stand mixer to roll and cut it to see if it’s better or worse. The stomping, however, is definitely happening again.

(For a more in-depth account of how I made this, you can find it in my Instagram stories here.)

What I’m Consuming…

Made with Lau is a series on YouTube in which Randy Lau documents his father, known as Daddy Lau, as he makes home versions of the dishes he made in his 50 years of restaurant cooking, first in Guangzhou, and since 1981 in the US. There are lots of familiar dishes to see (and make). Some are staples of small-town Chinese-American/Canadian restaurants and some are things you’d find in a larger Chinatown. It’s an endearing series dedicated to making sure these recipes are passed down to future generations. Each episode ends with the Lau family gathered around the table, eating the dish and adding additional details about possible variations and things to watch out for. As for the quality of the instructions? Here’s the result of my attempt at their Rainbow Chicken Stir-Fry:

Another YouTube series I’ve been watching a lot of lately is Dan Does from Eater, starring Daniel Geneen5.

It’s not an entirely novel concept for a series: guy goes to various food (or food-related) producers like Coppola Winery or Lodge Cast Iron and learns the ropes for a day. Along the way we get a How It’s Made look at what goes into the product we find on the shelf6. What differentiates it from other “inside the factory” shows is the host. Slightly goofy, he doesn’t play it cool when something strikes him as interesting or amusing. “Holy shit! This place is huge!” he calls out when he enters the barrel room at the Coppola winery. He’s an approachable everyman, but with a very different energy than Brad Leone’s doofus bro vibe.

What’s On The Menu…

Azumatei is an Mississauga-based ecommerce site for Japanese specialty foods. I discovered it when Musu Osaka Buns, a company started by a Japanese woman who moved from Osaka to Toronto in 2020, started selling her frozen pork- and bean-filled buns (very similar to Chinese bao) on the site. In an instagram message, she told me the butaman (pork buns) are very similar to the most famous ones in Osaka, made by 551 Horai. They’re perfect on a cold day and I’m excited to try them.

In order to qualify for free shipping at Azumatei I added a few more frozen things I have missed since I left Osaka, like grilled, salted mackerel fillets and, especially, katsuo tataki, a bonito fillet charred, usually over a hay fire and then sliced and served like sashimi.

The smoky char mixes with the meatiness of the raw bonito inside. Topped with grated daikon and green onion, then dipped in ponzu, it is one of my fondest food memories in Japan.

If you’ve seen the Osaka episode of Netflix’s Street Food: Asia, you’ve seen the chef with the massive blowtorch, Toyoji Chikumoto, preparing katsuo tataki at his stand, Izakaya Toyo. His first location was in a vacant lot about a mile up the road from my apartment, where on Saturdays he’d park his truck, set up a grill and a few tables to feed customers of the nearby pachinko parlours and off-track betting shop. If you wanted another beer, you got it yourself from a cooler. The chef would cackle as he fired up his torch and then start blasting more bonito. It was a raucous spot unlike anywhere I’d been7. I always knew it would be a great story and I fantasized about convincing Saveur to send me back to write about it. But in the intervening 18-ish years, Netflix snaked the story away from me! As I said in an earlier footnote, it can take me a long time to get to places, even when I’m very interested in them.

It looks like it was actually open for just under two years. It can take me a long time to get to places, even when I’m very interested in them.

There are lots of naming variations for this dish. Tsuji calls out the Namba neighbourhood of Osaka because it used to be a green onion-growing area. Now it is like Times Square.

A period of time where you leave the mixed ingredients alone so the water can more fully hydrate the flour.

I didn’t have any 1-gallon Ziploc bags. In Canada they are sold in sizes. I had XLs, but they didn’t look like a gallon to me. So I ordered some. They are exactly the same size.

It wasn’t until I saw the credits for the first episode I watched that I realized why Dan the host seemed so familiar: he’d been an intern at an agency I worked at around 2011. Halfway through the summer we realized that I knew a large chunk of his family. I had gone to grade school with his cousins. I’d met his father various times over the years and I ran into his aunt (my friends’ mother), food writing’s own Lucy Waverman, at Fiesta Farms a few years ago.

It’s not always a shelf. Sometimes it’s the fish counter, etc.

Or have been since.

The frozen udon at Sandown is quite good