53. How to be Cool in Japan

Don't be fooled into thinking the summer's over.

As I write this, the peak heat of summer seems to have finally broken in the last few days. I’ve had to wear jeans since yesterday and I’m not very happy about it. The forecast, however, says it should be back up to proper August temperature any day now. (In fact, as this is being edited, I am back in shorts.) I will not be fooled by the first of what will surely be several false falls!

That means that there is still time for summer food. More cobs of corn to be boiled, rolled in butter, and sprinkled with flaky salt.1 More perfectly red tomato slices nuzzled up against bacon, lettuce, and a generous swash of mayonnaise in toasty-crisp sandwiches.2 And, for me at least, more chances to have my favourite Japanese hot-weather foods.

Every summer I hit a point where I don’t want to cook. Or rather, I don’t feel like cooking much, because I want to minimize my exposure to heat as much as possible. I want things that, to paraphrase Satchel Paige’s How to Stay Young, won’t angry up the blood and will pacify the stomach with cool thoughts.

When I reached this point last year, exacerbated by my stubborn refusal to turn on the air conditioning during the daytime, a question popped into my head: “Why aren’t you drinking mugicha?” In the 22 years since I moved home from Osaka, this question had never occurred to me. Mugicha is barley tea,3 only it’s not actually tea. It’s toasted barley grains steeped in water until you have a mid-brown, slightly bitter, nutty drink that is incredibly refreshing when served ice cold. In the oppressively humid Osaka summer,4 it can be a godsend. And it’s naturally caffeine-free, so it won’t rile you up and cause you to get all sweaty again. How had I forgotten about it? Was it because of the comparatively mild Canadian summers? Was it only now because of global warming that I wanted it once again? And how could I get some?

Making mugicha is easy enough. Take a mugicha bag, toss it in a quart container, cover it with cold water, let it steep for a couple of hours, then discard the bag and refrigerate until it’s cool and refreshing. It’s a forgiving process. I have often forgotten and left the bag in overnight, only to discover that the resulting flavour was only slightly more bitter than it would have been if I were more attentive. But all of that presupposes that I had some on hand, which I did not.

In our last issue, you may remember5 that I showed you the three Japanese supermarkets in the Greater Toronto Area. The reason I wound up at all three in quick succession was because I was looking for mugicha. I didn’t see it at Sanko6 so I decided to take a trip down to Sandown, who had it on sale, no less. And then it struck me that if I also went to Heisei Mart,7 I might get a story out of it as well.

A nice thing about mugicha is that it’s a cold brew, so you don’t even need to run the kettle to make it. Let’s keep away from the stove again for our next heat-beater: hiyayakko.

Hiyayakko translates simply to “cold tofu,” but the story behind it is a little less straightforward. The “hiya” means “cold” and the second half refers to the servants (“yakko”) of a samurai. Apparently they wore a square crest representing a nail-puller on their vests that (somehow) resembled a block of tofu cut into cubes. (I know, it seems obvious once you explain it.)

The dish itself, similarly, is both straightforward or, if you choose, not as straightforward. First, drain your well-chilled silken tofu on a plate for a few minutes without pressing it, which will crush the delicate curd. 8

If desired, cut it into single portion-sized blocks and plate individually. The classic preparation for hiyayakko is to top it with sliced green onions; katsuobushi, or dried and smoked bonito flakes; and shoyu and garnish with a side of grated ginger.

There are also many variations for how it can be topped. The first, which is my go-to, is to swap ponzu for the shoyu. I love how the citrus of the ponzu complements the slight smokiness of the katsuobushi and bite of the green onion and ginger, as well as the cool, creaminess of the tofu.

Other serving suggestions I’ve seen include minced shiso leaf or lemon zest, grated daikon, baby anchovies, crab meat (or crab stick), corn kernels, cucumber slices, wasabi, plum paste,9 or sliced okra. However you choose to top it, it is a dish you need in a stultifying summer heat. Making it requires only as much effort and creativity as you see fit to muster and eating it will satisfy your hunger without overheating you or weighing you down excessively.

If you’re someone who has been turned off tofu before, I urge you to give hiyayakko a try. Silken tofu has such a mild flavour that the dish is much more about its coolness and texture. There’s none of the rubbery, overcooked omelet feel you sometimes find in cooked dishes. Cold silken tofu, flavour-wise, is merely a vessel for all of the tasty things you put on top.

You could probably cobble together an almost passable hiyayakko with any soft tofu, green onions, ginger, and shoyu (and maybe even ponzu) from your local Western or Asian supermarket. But for katsuobushi, which is essential, plum paste and shiso leaf and baby anchovies and everything else, you’ll need to hit a Japanese market. And, happily, all three spots in the last issue carry everything you’ll need.

The final of my favourites is zarusoba, cold noodles served with a chilled, soy-based dipping sauce on the side. Sadly, it needs the stove, but only for about seven minutes of cooking, plus however long it takes your stove to bring some water to a boil. (Just stand back from the heat as often as you can.)

Zarusoba starts just like all soba does: by boiling the noodles until just tender in lots of unsalted water. But then, instead of being placed into a bowl of hot broth and topped with things like deep-fried tofu wafers or tempura bits, they’re run under cold water to stop the cooking, drained, and neatly piled on bamboo10 mats called zaru,11 and topped with a pile of kizami nori (shredded seaweed).

It’s possible to make your own mentsuyu,12 the dipping sauce, but this requires more time at the hot stove as well as the ability to plan far enough ahead that it will be nicely chilled when you need it. I can’t be bothered with either.13 All of the stores I’ve mentioned sell pre-made sauce that you just take out of the fridge and pour into a bowl. The most common options for doctoring your sauce to your taste are wasabi and sliced green onions, although sometimes you also get a raw quail egg to mix in as well.14

You also might find restaurants that serve tenzaru soba, where your zarusoba comes with a side of tempura shrimp and possibly vegetables. Once again, my goal for zarusoba, as it is with most summer food, is to be near to heat for as little time as possible. Deep frying anything is antithetical to that goal, so it is only an option for me when eating out.15

Mix up your mentsuyu (be sure to get the wasabi well blended or you are in for a one-bite landmine at some point), lift a small knot of noodles from the zaru, give them a dip, and slurp away. Taste the cool saltiness of the sauce. The bite of the wasabi and onion, and the slippery chew of the noodles.16 Together, it’s all chilled and chilling, yet another cool thought to pacify your stomach without, most importantly, angrying up the blood.17

What I’m consuming…

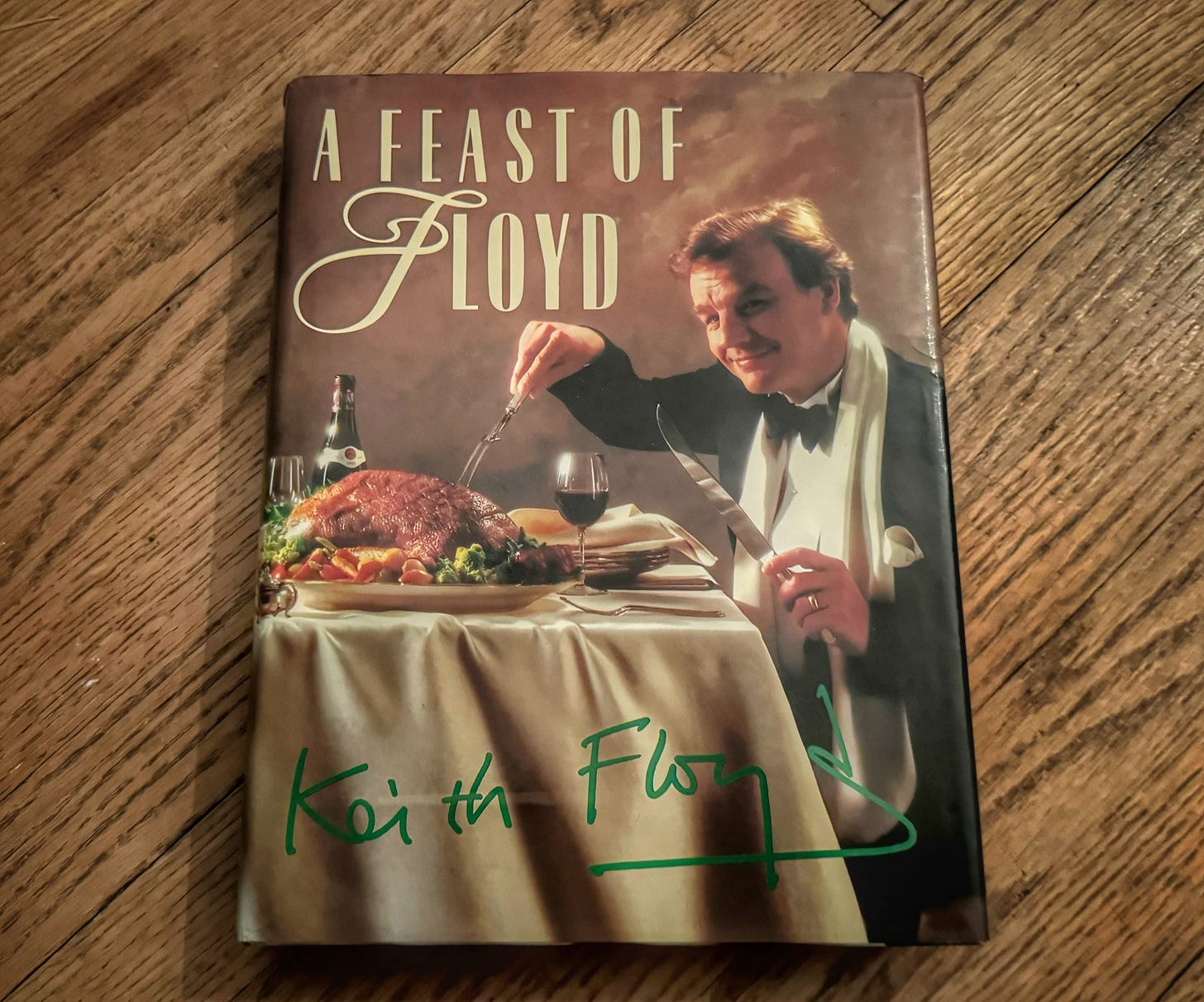

A Feast of Floyd by Keith Floyd — I first learned about Keith Floyd reading Stanley Tucci’s Taste: My Life Through Food but sadly never got to see the man in action before he died. I have devoured almost every clip I could find of his madcap, BBC-management-taunting, on-location cooking shows that were years ahead of his time. (I wrote more about him here.)

Until recently, though, I had never seen one of his books. That changed on a recent thrifting trip and now A Feast of Floyd is my current bedside reading. I’ve just finished the introduction, in which Floyd recounts in his singular, florid, and (almost certainly) wine-soaked voice just how he came to fall in love with food. I can’t wait to get into the recipes and, hopefully, make some of them.

What’s on the menu…

Nem Nuong (Vietnamese grilled sausages) — Although I’ve eaten these on numerous occasions in restaurants,18 it never occurred to me to make them until I happened upon a recipe from Samin Nosrat on the New York Times Cooking site. Further searching brought me to a recipe by Vicky Pham that intrigued me by calling for Tusino curing powder, essentially the Southeast Asian version of pink salt or Prague powder, which gives it its distinct flavour and red colour. I found some at my local Asian grocery store,19 but by the time I got home, dinner was running behind, so I wound up making Nosrat’s simpler version.

The skewers weren't really necessary, but they add a certain flair to the dish. (As does the mint leaf, no?) Stirring the meat mixture vigorously by hand for a minute and adding baking powder gave it a smooth, springy texture, but next time I will try adding the curing powder and following Pham’s recipe to see if it’s an improvement. I served them on some banh mi baguettes I picked up when I bought the curing powder, topped with mayo, herbs, and pickled carrot and daikon, but they would also be great over a bowl of rice or rice vermicelli.

Keep your changing leaves and Back-to-School sales. There is no surer sign that the end of summer is upon us than biting into an ear of corn and discovering that the walls of each kernel are just a bit thicker than they have been before and that your teeth can’t shear them from the cob quite as readily.

Also not a bad place for some flaky salt.

Mugi = barley, cha = tea.

The high in Osaka tomorrow (as I write this) is forecast to be 36°C with 98% humidity.

Good God I hope you do. It’s been less than a week!

They may have in fact had it. I have been known to suffer from the selective blindness that prevents me from seeing very not-non-existent things like my phone, my car keys, and that Ziploc full of Parmesan rinds I’ve been keeping in the freezer until assistance is available.

Who had it at an even lower price!

The woman at Sandown Market told me the silken tofu sold in shelf-stable, aseptic tetra packs was better for hiyayakko than the usual plastic tubs because it was much softer. I’ll say. The flavour was just as good, though.

I just tried adding plum paste for the first time when I made the hiyayakko in the photos above. Fantastic. Plum paste will be appearing in a lot of things from now on.

Traditionally. Many of the ones you see now are plastic.

Hence zaru = mat (actually “strainer”), soba = noodles

Men = noodles, tsuyu = dipping sauce. Who says Japanese is a difficult language?

That’s only half true. I can’t be bothered to make it myself. I lack the executive functioning skills necessary to make it in far enough in advance.

This is only in fancier establishments than, for instance, the one I’m running. Quail eggs? In this economy?

Raku, a restaurant I’ve written about before, does zaru udon (and ten zaru udon) with thicker wheat noodles instead of soba. All things being equal, I prefer zarusoba to zaru udon, but when it comes to Raku, things are definitely not equal. Their noodles are so wonderfully chewy and their broths and sauces so savoury and flavourful that there really is no comparison to making it at home. That part before where is said that using store-bought mentsuyu is better than making your own? It is, but neither is anywhere near as good as what they’re making at Raku.

And sure, the creaminess of the quail egg, Mr/Ms Fancypants.

Especially if you’ve blended your wasabi into the sauce well.

Along with the French, single-acting (almost all baking powder in North America is double-acting) Alsa baking powder she specifies.